By Jack Niedenthal

The Marshall Islands, a tranquil, remote chain of atolls in the Pacific Ocean, bears the haunting legacy of nuclear testing by the United States. Between 1946 and 1958, the U.S. conducted 67 nuclear and thermonuclear tests on Bikini and Enewetak Atolls, leaving a profound and lasting impact on our land, our people, and our generations yet to come. The most infamous test, the 1954 BRAVO hydrogen bomb, exemplifies the catastrophic consequences of these experiments, which persist to this day. (P-22) |JAPANESE| THAI|TURKISH|

Historical Context and Immediate Impacts

On March 1, 1954, the people of the Northern Marshall Islands awoke to an unprecedented event: Imagine living on a small, isolated necklace of tropical islands and watching the sun in the morning rise in the east as it always does… and then realizing that there is also a sun rising in the west. The BRAVO hydrogen bomb detonated in the northwest corner of Bikini Atoll, 1,000 times more powerful than the atom bomb dropped on Hiroshima at the end of WWII, vaporized 3 islands, sent the ash 100,000 feet into the atmosphere, and then showered the radioactive fallout over Rongelap, Utrok, and other neighboring atolls in the north. The islanders, unwarned and therefore completely unaware of the danger, had no idea what had just happened. The adults looked skyward in disbelief as the “snow” fell all around them, children played in the deadly ash, they all suffered immediate radiation sickness: burns, nausea, hair loss, and peeling skin.

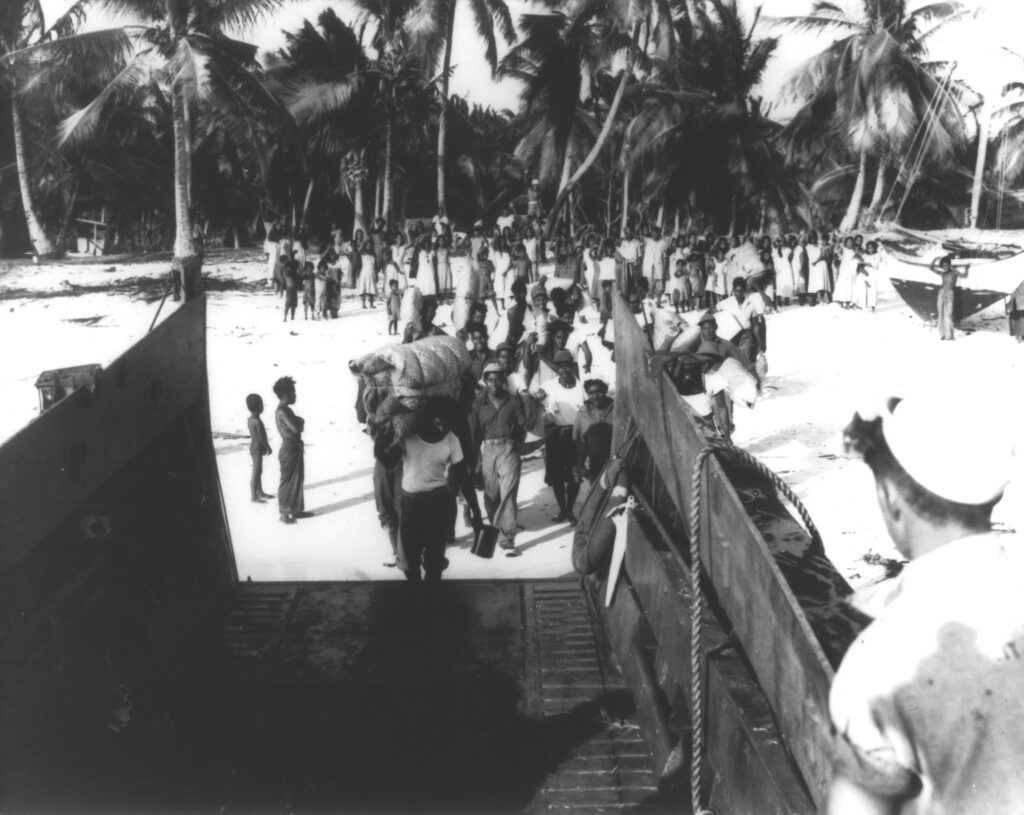

Despite knowing the direction of the prevailing winds, the U.S. failed to warn the Marshallese even though they told their own personnel in the area –stationed on ships and in fortified concrete bunkers– to go below decks and to stay out of harm’s way. It wasn’t until days later that the inhabitants of Rongelap and Utrok were finally evacuated. Many islanders endured lifelong health problems, especially thyroid cancers, and the fallout spread as far as a Japanese fishing vessel, killing one crew member and leaving others with acute radiation syndrome.

Environmental Devastation

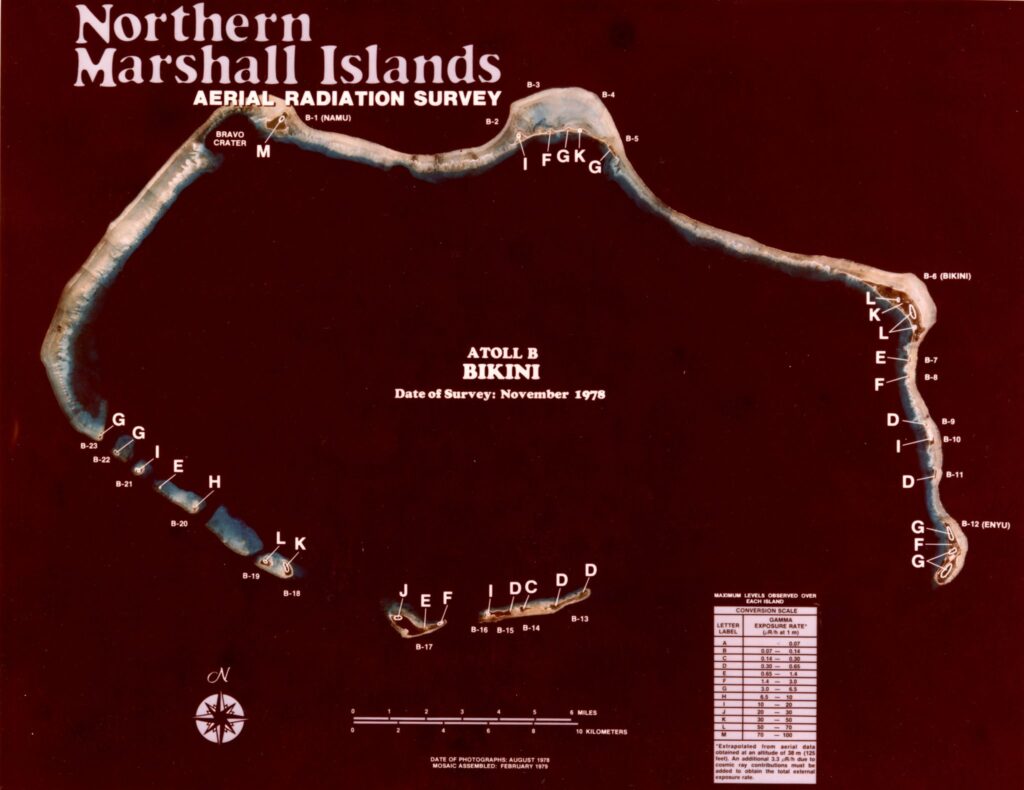

The nuclear and thermonuclear testing left the environment of the Marshall Islands deeply scarred. Bikini and parts of Enewetak Atoll remain contaminated, uninhabitable for the displaced communities. On Enewetak, the U.S. attempted a massive cleanup in the late 1970s, burying highly radioactive debris under the Runit Dome, a concrete structure now imperiled by rising sea levels. The Dome contains plutonium-239 and other toxic materials, a ticking time bomb threatening the Pacific ecosystem.

Desmond Doulatram, Co-Chair for the Liberal Arts Department at the College of the Marshall Islands, highlights the unresolved issues. “Many of our people saw the 70th anniversary of BRAVO last year as a painful reminder of what hasn’t happened. It’s about the restoration of our dignity,” he states, reflecting the enduring environmental and psychological wounds inflicted on the Marshallese.

Economic Consequences

The displacement caused by nuclear testing shattered the traditional livelihoods of the islanders. Forced relocations have left our communities dependent on foreign aid, living in overcrowded conditions often with limited access to resources. Attempts at resettlement, such as the early 1970s return to Bikini Atoll, a move encouraged in 1968 by then US President Lyndon B. Johnson on the front page of the New York Times, failed when it was discovered that the local food supply was highly contaminated with cesium-137. The people of Bikini were evacuated again in 1979, this time indefinitely.

The economic repercussions of these displacements continue to ripple through our island society. Limited infrastructure, inadequate health services, and a reliance on imported goods exacerbate the challenges faced by those displaced and their descendants.

Measures Taken: U.S. and Local Responses

The U.S. government has taken steps to address the legacy of its nuclear testing, though these efforts have been widely criticized as insufficient. Under the first Compact of Free Association (COFA) in the 1980s, $150 million was allocated for compensation. However, unpaid claims for land damage and personal injuries currently amount to over $2.2 billion. The Nuclear Claims Tribunal, created to adjudicate these claims, quickly exhausted its funds, leaving victims without recourse in the US courts.

Our leaders have worked tirelessly to seek justice. David Anitok, Senator for Ailuk Atoll and Envoy for Nuclear Justice and Human Rights, expresses the frustration felt by many Marshallese: “For a long time we’ve tried to get the U.S. to acknowledge what they’ve done… but they’ve always come up short of fully acknowledging what we sacrificed for the people of the United States and the world.”

Recent U.S. agreements under COFA III created a $700 million trust fund for the Marshallese people of 13 atolls for “Extraordinary Needs Disbursements,” yet critics point out that the word “nuclear” is conspicuously absent from the 57-page trust agreement. Jesse Gasper Jr., Senator from Bikini Atoll and Minister of Culture and Internal Affairs, insists that acknowledgment is crucial. “The U.S. needs to apologize. They need to acknowledge what they’ve done out here in the Marshall Islands from the office of the President of the United States,” he says.

Health Impacts and Generational Burdens

The health consequences of the nuclear testing era continue to unfold. Thyroid cancers, birth defects, and other radiation-related illnesses have plagued our population. According to a 2004 National Cancer Institute report, more than 530 cancers can be directly attributed to the testing, with many cases yet to manifest.

National Nuclear Commission Chairperson Ariana Tibon-Kilma, only 28 years old, represents the younger generation stepping into leadership roles. “I feel strongly that the overall nuclear legacy narrative should change,” she says, advocating for a more accurate portrayal of the widespread contamination. She also emphasizes the need for improved healthcare infrastructure, including access to specialists like oncologists and cardiologists. “Prioritizing healthcare is a form of justice that can benefit our entire population.”

Community Advocacy and Resilience

Marshallese communities have demonstrated remarkable resilience in the face of these challenges. Advocacy for nuclear justice has brought international attention to their plight. Greenpeace, along with figures like Darlene Keju, has played a significant role in amplifying the voices of victims. Keju’s husband, journalist Giff Johnson, remains a staunch chronicler of the nuclear legacy, pointing out that “the nuclear testing legacy doesn’t magically end at a certain date.”

Education is a cornerstone of the Marshallese response. Tibon-Kilma believes that a well-informed population is key to ensuring that the mistakes of the past are not repeated. “The more educated we are, the better choices we will be able to make,” she states.

The Path Forward

The road to justice and healing for the Marshallese people is long and fraught with obstacles. Acknowledgment of past wrongs, adequate compensation, and investments in health and environmental rehabilitation are essential steps. Improved healthcare facilities and environmental cleanups could pave the way for some of our communities to return to their ancestral homelands.

Furthermore, the Marshallese story serves as a powerful reminder of the global need for nuclear disarmament. By sharing their experiences, the Marshallese contribute to the broader movement for a world free from the threat of nuclear weapons.

Conclusion

The Marshall Islands’ legacy of nuclear testing is a sobering testament to the human and environmental cost of unchecked militarism. As our people continue their fight for justice, our story reminds the world of the importance of accountability, resilience, and the enduring human spirit. It is a call not only to remember but to act, ensuring that such atrocities are never repeated.

Author:Jack Niedenthal is the former secretary of Health Services for the Marshall Islands, where he has lived and worked for 44 years. He is the author of “For the Good of Mankind, An Oral History of the People of Bikini,” and president of Microwave Films, which has produced six award-winning feature films in the Marshallese language. Send feedback to jackniedenthal@gmail.com

This article is produced to you by London Post, in collaboration with INPS Japan and Soka Gakkai International, in consultative status with UN ECOSOC.